- Home

- Paul Guernsey

American Ghost Page 2

American Ghost Read online

Page 2

And, since this was my dog, I figured that the place where I found myself must also be my own—it was the house I shared with Chef and … two other bikers whose faces and various tattoos returned to me long moments before their names trickled back to whatever it was my mind had become. Mantis was one of the men, Dirt the other. This partial recovery of my identity and associations temporarily filled me with the cruel illusion that I might actually be returning to my natural life. Nevertheless, what a relief it was to know Tigre sensed my presence up there in that corner, a dimple in space surrounded by the dusty festoons of a former spider’s web! It was welcome proof that, despite the apparent fact that I was dead, something real remained of me. I experienced an emotion that might have made me cry, if I still had eyes.

Tigre: probably the only companion I ever had, aside from my mother, whose heart had never held even the tiniest taint of treachery. I then felt the first real hope of my afterlife: Maybe it would be possible for me to speak to my dog. But no sooner did this thought occur than I began to feel, for want of a better word, faint. I didn’t know it yet, but I was on the verge of being cosmically smacked down merely for thinking about breaking the most important of the many “rules” new ghosts are always stumbling over like tripwires. No sooner did my mind hatch this forbidden thought than light and color faded around me and that dark underground river began tugging me back to its depths. Tigre also seemed to sense a change. He whined again, more softly this time, and with a heartbreaking absence of expectation, after which he lowered his head, wheeled clumsily away from my corner and began his thunderous trot back down what I now knew was the short front hallway to my house, headed, no doubt, to his special spot on the braided rug in the bedroom he and I shared.

Had shared.

Out of desperation, I tried to call him back. But my effort had the effect of immediately snuffing my senses of vision and hearing and violently dragging me back to the currents of the dark and infinite river where I toppled and tumbled and was uncertain of anything except that I was somewhere, and wherever that vague place might be, it was very far from heaven.

CHAPTER 2

So I met Chef, I met Cricket, and not long afterward I left college to enter their shadowy world of rebellion and risk. I justified this reckless plunge by telling myself that I was gathering experience for a novel or a movie script, and that in due time I would retrace my steps to the light of my ordinary life. But the truth was, I had found a fascinating flame and I wanted to see how long I could hold my hand in it.

I was no biker, but I had been growing pot on a miniature scale since my Florida high school days, and I had a gift for inspiring the best in a bud. Within two months of that first night in the bar along the river, Chef and I had rented our rundown rural ranch house. Although it stood but a twenty-minute drive from the center of Riverside, the place had no close neighbors, and it contained a cellar roomy enough to raise a modest clandestine crop. Across the street from the house, there was nothing but a stretch of coastal swamp where the tassels of marsh grass waved in the wind. Behind us, beyond the wooden fence that surrounded our new backyard—and set about thirty yards into the woods past the boundary of our landlord’s property—sat an abandoned mobile home that Chef could convert into a methamphetamine kitchen. It was a perfect setup.

Chef was a competent hack chemist and a halfway decent motorcycle mechanic, but completely hopeless with a carpenter’s hammer in his sweaty, pink ham of a hand. As soon as the lease was signed, almost entirely by myself I pounded together a ventilated, soundproof shed in the backyard, guided in my work by a set of plans I had found in a particularly useful issue of High Times Magazine. The job took almost two weeks, and when the building was finished, we dragged in a brand-new, five-thousand-watt Honda generator. The purposes for this private power source were to cable juice to Chef’s trailer whenever it came time for him to don his vinyl elf suit and his respirator and brew us up a batch, and also to amp up my energy-intensive basement grow room, thereby avoiding the public power grid, where our consumption levels and telltale patterns of usage were apt to attract the unwanted attentions of the law.

Once the shed was up and the generator installed, Chef and I got down to business. I outfitted the basement with banks of grow lights, a powerful ventilation system, an irrigation network, and a state-of-the-art, temperature-controlled drying closet. I sowed our first crop, which consisted of several cannabis strains whose array of magical properties had fired my curiosity. Then I acquired Tigre, half-grown at the time, and began training him as our chief of security. I also took time to establish an elaborate bird-feeding station in the backyard: I’d always been a birder, and in college, as a budding biologist, I had given serious thought to specializing in ornithology.

To my surprise, Cricket did not immediately move in with us; instead, she spent no more than three or four nights a week at the house and behind the closed door of Chef’s bedroom. But we did soon bring in another housemate—a greasy worm of a biker named Dirt whom Chef dragged home from the bars one night, insisting that he would make an ideal and unquestioning helper and deliveryman for both of us. And that he mostly was—though on several occasions we almost kicked him out for dipping into the crystal. Our number one household policy was that any of us could smoke all the weed he wanted, but touching the crank—even just to “taste” it—was out of bounds. It’s no secret that meth fucks people up; not only does it turn tweakers into gargoyles, but it makes them do irrational and dangerous things. Chef and I certainly did not want anything like that going on around us.

One time when Dirt had been tweaking and did something I considered especially destructive and stupid, I beat the shit out of him for it, and wound up knocking a tooth right out of his dumb skull. He was lucky I didn’t kill him. But more about that later.

*

About a year into our operation, we took on yet another associate and this completed our crew. The new dude was a tall, bearded, and seemingly capable biker named Mantis who had come to us from Arizona after abruptly resigning his membership, under circumstances he refused to discuss, in a chapter of one of the big, one-percenter clubs. All he would tell us about his flight from the Southwest was that he had been a chapter officer, and that there had been some accounting errors for which he was unfairly held responsible. Although it was strongly rumored that to become a member of Mantis’s former club you had to have intentionally killed somebody, when he first presented himself to Chef and me, his demeanor was mild, almost meek, and we decided what the hell, anyone deserved forgiveness and a second chance.

From the time of his arrival it was apparent that Mantis also had eyes for Cricket. But by then Cricket had already made the jump from Chef’s futon to my bed. When it happened—after she broke the news to Chef as gently as she could—I really did expect that everything we’d built would fall apart. I’d been prepared for threats, breakage, and maybe even some actual, wild violence. To be honest, I was excited about the prospect.

But Chef merely disappeared for a little more than a week, and after he came back, he carried on as always. The only hint of how badly he was hurting was that it took several days before he was able to look either of us in the eye. Later, Cricket and I concluded that he had reacted with such a surprising lack of drama because, not only did he have nowhere else to go, but from the start he’d understood that his luck with her would likely never last. All along, he’d been braced to see her swap him out for someone more like me.

*

The second time I returned to the land of the living, I found myself back up in that dusty corner above the front door to my house. The same cobwebs undulated before me and the empty hallway gaped below. I could “see” down the hallway into the living room and through the window curtains into the fenced-in backyard; in fact, when I concentrated, I could peer right through all the surrounding walls as if they were panes of dirty glass, a superpower I employed at once to locate Tigre, who was sleeping in my bedroom. Still far from fully illu

minated as a ghost, I remained without arms, legs, or head. I wondered whether I might at least be able to leave my corner and motor to some other part of the house. Wondering led to effort, effort led to successful movement, and soon I set out on a slow, firefly-like flight.

I navigated into the kitchen, where I had already sensed that things had been screwed with. Sure enough, gone was Chef’s alchemical assortment of methamphetamine manufacturing supplies, most of which, between his visits to the trailer, he had stored in cardboard boxes and bags on our kitchen floor and counters. The missing stuff included the mounds of bubble-packaged, pseudoephedrine-based cold and allergy remedies Chef used as a primary ingredient, as well as the gallon and half-gallon containers of ammonia, muriatic acid, paint thinner, Red Devil lye, and Drano, along with the smaller bottles of such explosive or corrosive chemicals as starter fluid, brake fluid, lighter fluid, and hydrochloric acid. Also gone were the veterinary-size bottles of iodine tincture, the neat boxes of highway flares waiting to be broken apart for the red phosphorous they contained, all the laboratory gear, including the flasks and mason jars and other glassware, the coils of transparent tubing, the three-burner portable gas stove, and Chef’s assortment of plastic tubs, buckets, and bottles.

I guessed that everything had been taken away as a precautionary measure. Either that or the house had been raided by someone—by the cops or a group of our business rivals. But of the two possibilities I thought precaution was the better bet, since there was no evidence of an invasion: no disorder, breakage, or rust-colored traces of blood. In fact, the kitchen looked tidier than usual, not only because the meth-lab inventory was gone, but also because our meager assortment of plates and bowls was stacked in the cupboards rather than piled in the sink, soaking in a greasy slick of water.

As I hovered there midway between the ceiling and the floor, Tigre thundered into the kitchen from the hallway that led down to the three bedrooms and the bathroom. He searched for me, whining and turning himself around, his thick black claws clicking against the linoleum. Clearly, he had no idea where, exactly, I was, and maybe did not yet even know who I was; he may merely have sensed a disturbance and been seeking its source. In any case, right then I had no time for him, because the absence of Chef’s gear made it likely that they had also taken things that belonged to me.

Tigre made a nearly subsonic rumble in his throat as he followed me to the basement door. Of course, I couldn’t turn the doorknob—but no longer was that door, or any door, a barrier to me: I passed right through it with no resistance save for a vague, overall prickling sensation that brought back a vivid childhood memory of pushing headlong through a wool curtain pregnant with static electricity. I found myself at the top of the wooden cellar stairway—Tigre barking behind me now with a growing alarm that was edging toward hysteria—and immersed in what would have been total darkness if I still had eyes. In a slow, dream-like beeline, I followed those stairs into the basement room where, ever since quitting college nearly two years before, I had spent most of my days conducting an all-female orchestra of various cannabis strains, each of them superbly bred, trained, and groomed to play her own special melody in the human imagination.

But now the cellar was empty not only of my strings and woodwinds and brass—my oboes and my clarinets, my cellos, violins, and xylophones, my tympani, all of which comprised the individual, distinctive voices of my sweet, beautiful, large-budded ladies—but also of every scrap of hardware and any other hint that I myself had ever existed. Not a screw or coupling or speck of planting medium remained; it was clear that they had carefully swept the concrete floor in order to obliterate every last, incriminating particle. This large portion of my life’s work—my vineyard, my orchard—had been uprooted, burned over, and plowed under, and with it a major part of the person I had been.

I hovered there until I began to feel pathetic and then, without having to turn around I retraced my path up the stairs and through the door. I could as easily have ascended directly between the ceiling joists and through the plywood floor, but stairs were still a habit.

Tigre quit his barking as soon as I rejoined him. He whined and seemed to look directly at me as I passed like Tinkerbell above his wet boulder of a nose, and I was gripped by an almost irresistible urge to speak to him. But I did not dare: not only did I remember the unpleasant result of my last flirtation with this idea, but just the thought of causing the air to vibrate with the sound of my voice scared me to the point of blacking out.

I prickled my way through the rear wall of the house and into the fenced-in yard that contained, along with a few scattered and toppled plastic lawn chairs, Tigre’s exercise equipment, my ambitious array of birdfeeders—all of them empty, and abandoned by the birds—and my generator shed. The wind was blowing, rain threatened, and the dry leaves of red maples cartwheeled through the air, each one making a tick as it touched the grass. It bothered me to learn that the strong wind had absolutely no effect on me; I could sense it only through the life I saw it give to objects such as leaves, and could feel neither its force nor its chill.

I knew the generator shed would be empty; they’d have dragged off my powerful Honda along with everything else. No reason to strain myself by peering through the wall. However, the shed did hold something else I valued: Over the course of two years, between scribbled columns of coded business notes, I had penciled several dozen poems on the shed’s naked sheetrock walls. I was about to pass through the wall and reread them all when a whine from Tigre, followed by the sound of a familiar car turning into the driveway, drew me back to the house.

Tigre was standing before the front door, the stump of his tail twitching in excitement. A moment later the lock turned, the front door swung open, and my beautiful girl, Cricket, stepped in and dropped to one knee to hug my dog and murmur something into his neck just above the nasty spikes of his collar. Then she was on her feet again and her birdlike legs went scissoring into my bedroom, which she had sometimes shared with me, and where she now began tossing her way through the drawers in my two dressers. Each time she finished with one drawer, she slammed it shut and moved on to the next.

As I watched her work, I was happy to find that I could still feel many human things: I was glowing with nostalgia and affection mixed with some regret. What Cricket and I had most in common—had had most in common—was our mutual dedication to downward mobility. In another life, her name was Claire, and she was the daughter of a dentist—the adopted daughter of a dentist, as she was often quick to point out. In addition, I believed—based on intuition rather than evidence—that she, like me, was part Hispanic, though Cricket herself had been unable to say for certain what her heritage was.

Tigre barked, and I heard the rumble of Mantis’s Harley-Davidson Softail coasting into the driveway. Cricket heard it too; she stiffened, shoved the last drawer shut, and hurried out to the living room, where she dropped onto the couch and began feeling around in the pockets of her leather jacket. After a moment, she produced a crumpled pack of cigarettes and tossed it onto the coffee table.

Tigre growled at Mantis in the doorway.

“Shut up,” said Mantis quietly, and Tigre fell silent. A moment later he said, “Fucking dog’s got to go.” He looked up at Cricket, the two of them silently and expressionlessly locking eyes for a long moment before Mantis broke away and clumped around into the kitchen and down the hall to my room, where he conducted his own, more thorough, though apparently just as fruitless, search of my earthly possessions. Unlike Cricket’s almost respectful rifling, Mantis scattered my clothes onto the floor, and he sent the vacant drawers crashing.

After he was finished, he returned to the living room, plunged his lanky frame into the couch next to Cricket, and kicked his heavy, black boots onto the coffee table. After a moment he rested his elbow on the back of the couch, pressed a tattooed fist into his beard, and stared at her in a way he would never have dared when I was alive.

“So, like, what were you looking for?” Cric

ket’s voice was a note higher than normal.

Instead of answering, Mantis mimicked her tone, saying, “So, like, what are you doing here?”

Cricket drew a Bic lighter from within her jacket, her pale hand trembling slightly. Then she picked up the cigarette pack as if she were about to shake one out. Instead, she seemed to reconsider and ended up setting both the lighter and the cigarettes back onto the tabletop. She told Mantis, “The cops came to see me at work today. Spent a half hour talking to me down in the parking lot.”

“Well, ain’t that a coincidence? They came to look for me at Pete’s. They weren’t friendly, either. They did not seem sorry for our loss.”

Cricket took up the lighter again and turned it over and over in her fingers before giving it a couple of idle flicks. “I don’t get it. Why don’t they just come and search the house? Get it over with?”

“No corpse yet, I guess,” said Mantis. “That’s what they’re waiting for, I bet. Nothing but his empty truck, burned up in a quarry. Those three photos of him lying there dead that turned up online; maybe they’re thinking that blood was ketchup and that he faked his own death, or something. If they ever find a body, I bet they’ll be here in an hour.”

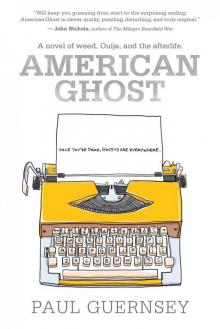

American Ghost

American Ghost